A review of the above titled paper by Hugh

Doulton, Katrina Brown.

Climate change is, rightly or wrongly,

still a contested issue in all its dimensions—scientific, political, economic

and social (Carvalho, 2003). The mass media is a critical arena for this

debate, and an important source of climate change information for the public. The

science of climate change is full of uncertainty, however, the greater

vulnerability of poor countries to the impacts of climate change is one aspect

that is widely acknowledged.

The paper adapts Dryzek’s (2005)

‘components’ approach to discourse analysis to explore the media construction

of climate change and development in UK ‘quality’ newspapers between 1997 and

2007. Eight discourses are identified from more than 150 articles, based on the

entities recognised, assumptions about natural relationships, agents and their

motives, rhetorical devices and normative judgements. They show a wide range of

opinions regarding the impacts of climate change on development and the

appropriate action to be taken.

The term ‘discourse’ has many definitions;

here it is understood as ‘a shared meaning of a phenomenon’ (Adger et al.,

2001).

Discourses concerned with likely severe impacts

have dominated coverage in the Guardian and the Independent since 1997, and in

all four papers since 2006. Previously discourses proposing that climate change

was a low development priority had formed the coverage in the Times and the

Telegraph.

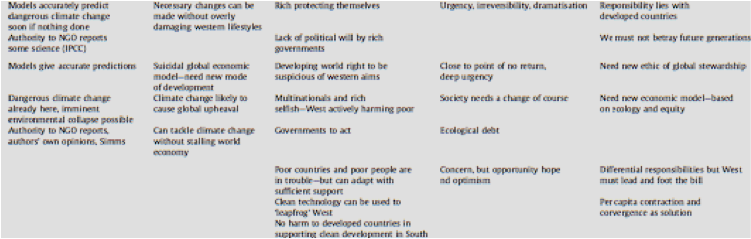

The classification of different discourses

allows an inductive, nuanced analysis of the factors influencing representation

of climate change and development issues; an analysis which highlights the role

of key events, individual actors, newspaper ideology and wider social and

political factors. Table 1 below gives a summary of the 8 different discourses.

(Click on the table for a better look, both images contribute to the same table). The table displays how they are distinguished and how they

are constructed through the basic entities recognized; the assumptions about

natural relationships; the agents; metaphors and rhetorical devices; and

normative judgments. The sources of authority range from climate/skeptical

science, to NGOs and individuals.

|

| Table 1. |

Authors have shown that the media

frequently fails to convey scientific uncertainty regarding climate change

accurately, tending to sensationalism and increased certainty, despite major inherent

uncertainty in climate predictions (Ladle et al., 2005).

In all the discourses other than optimism and self-righteous mitigation (table 2.), developing countries are

portrayed as needing the help of the developed world if they are to deal with

the impacts of climate change. There is little discussion of poor people in

dealing with the impacts of climate change, nor the complex interplay of

factors that will influence the vulnerability and adaption to climate change (Adger

et. al., 2003). Only ‘disaster strikes’ gives

any voice to poor people, as well as barely any differentiation of the varied

developing world itself.

Thus the overall the findings demonstrate

media perceptions of a rising sense of an impending catastrophe for the

developing world that is defenseless without the help of the West, perpetuating

to an extent views of the poor as victims.

References

Adger, W.N., Huq, S., Brown, K., Conway,

D., Hulme, M., (2003). Adaptation to climate change in the developing world.

Progress in Development Studies 3 (3), 179.

Carvalho, A. (2003). Reading the papers:

ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge. Paper

presented at a conference entitled Does Discourse Matter? Discourse Power and

Institutions in the Sustainability Transition, Hamburg, Germany, pp.11-13.

Dryzek, J.S. (2005). The Politics of the

Earth: Environmental Discourses. Oxford University Press.

Ladle, R.J., Jepson, P., Whittaker, R.J.,

2005. Scientists and the media: the struggle for legitimacy in climate change

and conservation science. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 30 (3), 231–240.